This article discusses a classic trade-off between procedural programming and object-oriented programming, presented by Robert C. Martin in Clean Code, through the anti-symmetry between data structures and objects.

Context and Terminology

Before we dive into the topic, we need to pin down what we mean by some of the terms we’ll be using here.

What are Data Structures

Data structures expose their data and don’t have any meaningful behavior. The purest form of a data structure is a class/struct with public variables and no functions at all. That object is called a DTO (Data Transfer Object).

It’s important to be clear that, in the context of Clean Code, “data structure” does not mean arrays, lists, or trees, but objects whose only job is to carry data.

And what about Active Records?

According to Uncle Bob, in Clean Code, Active Records are special forms of data structures. They expose their data directly and, although they have methods like save() and find(), those methods are limited to data persistence and navigation.

Even though they’re often treated as objects, Active Records don’t encapsulate business rules or protect invariants. For that reason, they should be treated as data structures, not as domain objects.

What are objects

Objects hide their data and implementation details behind abstractions, and expose functions that operate on that data.

The antisymmetry between Data Structures and objects

In short, what’s easy for one is hard for the other. Just as procedural code makes it easy to add new functions without changing existing data structures, it makes adding new data structures very hard, since that would require changing all the existing functions.

Object-oriented programming flips this around: it makes adding new classes trivial, but makes adding new functions harder, since that new behavior would have to be implemented across all classes.

A real-world example

To make the difference concrete, let’s think about a freemium app.

This app needs to:

- Know whether a feature is enabled;

- Calculate permissions;

- In the future, add new rules or new user types.

With that in mind, let’s implement both approaches and see how they differ.

Case 1 – DTO + procedural code

Session as a DTO (zero behavior, just state)

struct SessionDTO {

let isLoggedIn: Bool

let isAdmin: Bool

let hasPremium: Bool

let country: String

}

Procedural logic:

struct SessionRules {

static func canAccessPaywall(_ session: SessionDTO) -> Bool {

session.isLoggedIn && !session.hasPremium

}

static func canAccessAdminPanel(_ session: SessionDTO) -> Bool {

session.isLoggedIn && session.isAdmin

}

static func canUseFeatureX(_ session: SessionDTO) -> Bool {

session.country == "BR" && session.hasPremium

}

}

Advantages

If we want to add a new method like canUseFeatureY(), we just implement it in SessionRules:

static func canUseFeatureY(_ session: SessionDTO) -> Bool { ... }

Drawbacks

To make the example clearer, we’ll stick with the same procedural approach, but evolve it to support multiple types.

Imagine we need to add a new session type to our app — for example, a sandbox user session.

// The protocol here does not represent domain polymorphism,

// just a base type for data transport.

protocol Session {

func logout()

}

struct SessionDTO: Session {

var isLoggedIn: Bool

let isAdmin: Bool

let hasPremium: Bool

let country: String

}

struct SandboxSessionDTO: Session {

var isLoggedIn: Bool

let country: String

}

So far, everything looks fine. But because of the new session type, we now have to change the methods in SessionRules:

struct SessionRules {

static func canAccessPaywall(_ session: Session) -> Bool {

if let user = session as? SessionDTO {

return user.isLoggedIn && !user.hasPremium

} else {

return false

}

}

static func canAccessAdminPanel(_ session: Session) -> Bool {

if let user = session as? SessionDTO {

return user.isLoggedIn && user.isAdmin

} else {

return true

}

}

static func canUseFeatureX(_ session: Session) -> Bool {

if let user = session as? SessionDTO {

return user.country == "BR" && user.hasPremium

} else {

return true

}

}

}

Case 2 – Object-oriented programming

For this kind of implementation, we need to declare an object along with its behavior. This could be done with class inheritance, but here we’ll use protocol + struct.

protocol Session {

func canAccessPaywall() -> Bool

func canAccessAdminPanel() -> Bool

func canUseFeatureX() -> Bool

}

Then we define the session types with their specific implementations:

struct GuestSession: Session {

func canAccessPaywall() -> Bool { true }

func canAccessAdminPanel() -> Bool { false }

func canUseFeatureX() -> Bool { false }

}

struct PremiumUserSession: Session {

func canAccessPaywall() -> Bool { false }

func canAccessAdminPanel() -> Bool { false }

func canUseFeatureX() -> Bool { true }

}

struct AdminSession: Session {

func canAccessPaywall() -> Bool { false }

func canAccessAdminPanel() -> Bool { true }

func canUseFeatureX() -> Bool { true }

}

Advantages

It’s very easy to add new objects in this model. Just create a new struct/class, make it conform to the protocol, and implement its methods.

Drawbacks

If we want to add a new method to the protocol or change an existing one, we’ll need to update every object that implements it.

protocol Session {

func canAccessPaywall() -> Bool

func canAccessAdminPanel() -> Bool

func canUseFeatureX() -> Bool

func canUseFeatureY() -> Bool

}

That small method addition above would force changes in the other three structs that conform to the protocol.

Comparing the approaches

If you expect to add new types frequently, object-oriented programming tends to minimize the cost. On the other hand, if you expect to add new operations more often, a procedural approach may serve you better.

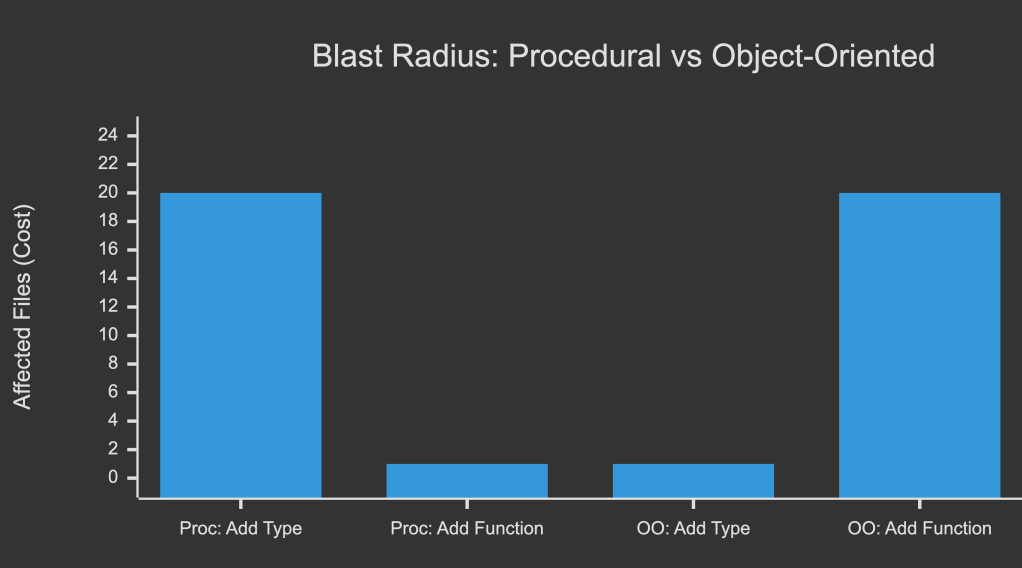

To express these differences mathematically, we can use blast radius to define the number of touched points:

And then define the canonical changes:

Legend:

- E: set of entities (types / variants)

- O: set of operations (rules / functions / methods)

- Δe: change that adds a new entity (e)

- Δo: change that adds a new operation (o)

- α: fraction of operations affected by the new entity

- β: fraction of entities affected by the new operation

This fundamental inequality (anti-symmetry) is precisely the inverse relationship between maintenance costs.

| Operação | Procedural (DTO) | Orientado a objetos |

|---|---|---|

| Adicionar função (+$F$) | Fácil | Difícil |

| Adicionar tipo (+$T$) | Difícil | Fácil |

Conclusion

The choice is not between good and bad, but between which axis of change brings more value to your system. The key point is understanding that, regardless of the paradigm you choose to solve this problem, there will always be a trade-off: a weakness in one approach becomes a strength in the other, and vice versa.

Leave a comment